The conversation about finding a partner typically goes something like this: It should be a selfless act. For Eugene Sepulveda, that doesn’t hold water. “It should be completely selfish. It’s not sustainable otherwise,” he said. “I identified that Steven would help me realize who I wanted to become, and I could help him. The nonselfish part is that it was equally important for me to know that I could help him.”

Sepulveda’s first date with Steven Tomlinson, his partner of 13 years, was spent strolling the tree-lined streets of Clarksville, where they began a conversation that has continued to this day. They ultimately realized what unites them: community, family and sparking conversations that move the needle forward in a city.

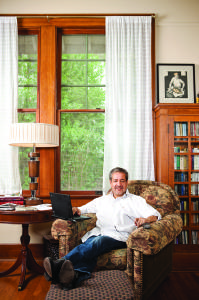

Eugene Sepulveda & Steven Tomlinson

Photo by Michael Thad Carter

Tomlinson emphasized that while they both care about building community, they approach it in contrasting ways. The more introverted of the two men, Tomlinson labeled himself a “frustrated pastor” and said that Sepulveda, more extroverted, is more of a “frustrated politician.” Approaching the issue from different angles, the couple always hoped to influence positive change, build connections that last and promote civic engagement.

Most people don’t have a serious idea of what combination of factors draws them to their boyfriend or partner, despite countless relationship advice columns and self-help books. It’s the very intangibility of love and attraction, and our natural inclination as humans to seek companionship, that makes the chase enjoyable and prompts couples to discover the reasons for their commitment.

“We committed to each other with faith that it was right, and that’s hard to have confidence in because I can usually reason out what I’m doing,” Tomlinson said. “But we’ve spent almost 13 years unpacking the promise of our original enthusiasm for being together.”

Years earlier, Sepulveda had written in his journal that if he was going to settle down–he enjoyed being single–his other half would be a scholar, a theologian, an artist and tall. “After the seventh month, we didn’t have an argument that risked the relationship,” Sepulveda added. Indeed, in a wide-ranging conversation at their home in Aldridge Place/Hemphill Park, the two men were at ease with the type of casual, back-and-forth banter that’s typical for couples who are confident in their relationship.

Nevertheless, every relationship has its own set of challenges and promises. This is particularly the case for gays and lesbians, often operating without a fixed model or blueprint for how to form relationships and what rules to set up (or remake) to maintain those relationships. It’s natural for younger people to seek guidance from their older, partnered friends. For Sepulveda and Tomlinson, keeping it simple was the best choice.

The two men made three telling promises to each other at their intimate May 2000 commitment ceremony, held at the home of a couple (two of their best friends, Jill McRae and State District Judge Stephen Yelenosky) celebrating 10 years together, in front of their core friends: They agreed to tell each other the truth, to be faithful, and that they would take care of themselves for the sake of their common goals.

The event was officiated by an Episcopal priest who is a friend of theirs, and guests had plenty to say about the couple’s promises to each other. “There are lots of different relationships in the community,” Sepulveda said. “The challenge in all of those is about telling the truth: not because you want to lie, but because you have to tell yourself the truth first.”

Tomlinson had closed on the first house he ever bought on April 30, the same day of that first date in Clarksville. But, Tomlinson didn’t move in to the house for another three months; Sepulveda moved in that same day. It’s one story that they tell a little bit differently.

Early evenings together would become late nights talking and getting to know each other. One particular night, at about one o’clock in the morning, Tomlinson told Sepulveda that he needed to go home, so he did. Only four hours later, however, Sepulveda returned and it was pretty clear that for all intent and purpose, they were already living together–they didn’t want to be apart from each other. “I came home from school and Eugene had moved in,” Tomlinson said, smiling. “He kind of came with the house. I don’t remember us ever having a discussion about it.”

Together, with their personal openness as a couple and professional output in various business and nonprofit endeavors, they are a formidable force for change, social justice and LGBT equality. When the conversation turned to the ongoing struggle against discrimination and the fact that in 29 states you can still be fired for being gay or lesbian, Sepulveda was direct.

“I’d rather us take the shrapnel, because we’re in a position, where, one, a lot of people won’t mess with us,” he said, adding: “We forget that there are still people who [aren’t comfortable being out] and colleagues don’t know that they’re queer.”

Being open about their relationship, and, when needed, stirring the pot, has reaped countless rewards for the couple, including at St. James Episcopal Church, where Tomlinson had been a member for 10 years when he met Sepulveda. When they began attending as a couple in 1999, Sepulveda wanted to sit in the front row, to force any conversations that needed to happen out into the open. As it turned out, there were some objections at the historically African-American church in East Austin.

As a way to open up a dialogue and bridge any gaps that existed, a friend recommended that they do Bible study with the churchgo- ers who had objections. For 12 weeks every Sunday, for an hour or so before the service, they met and talked about what the Bible has to say about homosexuality. Not long after, attitudes shifted. “We capped it off with brunch at our house, and by then, everyone that had an objection, their minds changed,” Sepulveda said. “It took that kind of deliberate discussion.”

For Tomlinson, the issue was less about receiving the church’s imprimatur on their relationship and more about having the wholeness of their life together, as a couple, be appreciated. Indeed, the blessing of same-sex unions is one that the Episcopal Church, like many other communities of faith, is still grappling with and will likely be addressed at its upcoming 2012 General Convention.

“The church is quite happy to use my talent or my resources for the sake of its mission, but not recognize that anything I have that’s any good comes from the love that Eugene gives to me, which gives me confidence to take risks everyday, which affirms to me that life is worth living, which builds these gifts up,” said Tomlinson. “This relationship is already blessed by God, all we can do is see whether we want to recognize that or not.”

However, the couple’s decision to tie the knot on Salt Spring Island, Canada, was about the many official responsibilities that marriage entails. In that country, they are legally responsible for one another (in areas of finance or in case of medical emergency, for example). They chose Salt Spring Island, which is one of the Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, for its gorgeous setting and the bond they have with friends who own a house there and because, for several years, they spent a large part of their summers there.

“We wanted to codify it legally. This is a very beautiful part of the world and we have some very dear friends there,” said Sepulveda. “It turned out to be monumental: having that piece of paper and being able to write married on customs forms when you enter and exit other countries.”

EDUCATION, and the opportunities it provides, has been a powerful catalyst for both men. They both derive immense satisfaction from igniting the intellectual curiosity of college students and younger people in general. Sepulveda, born in Houston and raised in a working-class environment, was the first of his family to attend college. He went on to graduate from Texas A&M with his bachelor’s degree in business administration. Tomlinson, a native of Oklahoma, studied economics at the University of Oklahoma and earned his PhD in economics at Stanford University.

Sepulveda, whose easygoing manner and modest attitude belies all that he’s accomplished in the city, has a professional life that has touched and uplifted a wide range of companies and nonprofits in Austin. Having served on the boards of more than 75 non- profits, for-profits and foundation boards over the years, he’s the man that many people turn to locally when their organization needs a lift. His role as CEO of Entrepreneurs Foundation of Central Texas, which he has held since April 2005, puts his skills of connecting like-minded individuals and building community to good use.

“We’re all about bringing intellectual and financial capital to make our communities better,” Sepulveda said. “We’ve helped raise over $7 million for other nonprofits and we’ve also helped form business, community and government partnerships to advance breast cancer services in Central Texas and affordable housing in East Austin.”

When Sepulveda was elected chairman of the board of Leadership Austin in 1999, he gave a speech stating that Austin could be one of the great cities of the twenty-first century. “I meant that if we could hold onto what made us great, then we would be great. It’s not easy to hold onto a diverse arts community and to still provide economic opportunity. But if you continue to have this huge economic chasm, with more and more people who have nothing, and more people who have a lot, then it’s going to change.” Even so, he added that the city is “very equipped” to deal with these challenges.

“It’s up to us to hold the conversation up to a level that appeals to the best part of people,” said Tomlinson. When Tomlinson arrived in Austin, he was an assistant professor in the economics department at the age of 28, which was a considerable achievement, but something was missing. Like most people in their twenties, he was still searching for his truth and pursuing his creativity. He’d read about an open mic night for storytellers at a place called Chicago House. Sitting in the back of the room, he hadn’t brought a script or prepared any monologue, but when the woman who ran the session told him he had to perform or leave, he didn’t hesitate. Tomlinson shared a story he used to tell about his family. Every Thursday night, he’d come home from teaching at the Acton School of Business, and would create a monologue that he performed based on the notes he’d kept all week. Not long after, he was asked to do a showcase with several of his short pieces. The woman who ran Hyde Park Theater at the time saw him and offered to produce his work. His plays, which are frequently autobiographical and have been performed locally at Frontera Fest and off Broadway in New York City, have won national recognition from the American Theatre Critics Association and touched on subjects ranging from the North American Free Trade Agreement to the problems plaguing the health care system. American Fiesta, which was produced in 2005 and won the ATCA’s Osbourne Award for Best New Play by an emerging playwright, is a poignant and uplifting meditation on the power of family bonds–and our ability to overcome difficulties in those relationships–while also touching on same-sex marriage and the collection of vintage Fiesta dinnerware.

With 16 years of teaching under Tomlinson’s belt, including time spent at the Episcopal Seminary where he taught a course on the “Spirituality of Money,” it’s no surprise that he finds the nuts and bolts of academics to be enormously rewarding. “My journey as a teacher has been to start with students and ask what they are trying to accomplish. That informs me and excites me.”

One area that unites their common interests and driving passions (improved health care, growing economic opportunities, expanding the arts, and strengthening the environment) is working on behalf of President Barack Obama. Sepulveda serves on the national finance committee and as co-chair of President Obama’s LGBT Leadership Council. Thus far, he’s raised more than $1 million for Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign and was listed as one of the president’s top 25 fundraisers nationwide in the most recent FEC filings. However, Sepulveda pointed out Tthat he has supported Republican candidates as well.

Their journey as gay men, coming into their own professionally and personally, were very different. Sepulveda, who worked in banking and finance for the better part of two decades, always assumed that his sexual orientation would eventually lead to his being blackmailed by a coworker.

It’s a fear that many gay men and women had in the past–and still have today. During the “Lavender Scare” in the 1950s, which paralleled the anti-communist campaign of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, U.S. government officials felt that gay men and women were susceptible to blackmail and therefore were security risks. In the largely conservative world of finance, Sepulveda’s fears were warranted.

“I planned to gather evidence on them, submit it to the FBI and then commit suicide,” said Sepulveda, adding that his plan seemed fairly logical, given the times in which he was living.

When the incident did occur, Sepulveda was confronted by someone who had seen him at a gay bar in San Antonio, who then tried to shake him down for $500. “I just laughed because I always assumed someone would try to get me to give them a million dollars–I laughed and was like, get out of here! It was an incredible relief for me to get past that.”

Coming out to his family in his early thirties was not as dramatic. Adamant about what his expectations were, he said that he didn’t want to be treated any differently than his siblings because of his sexual orientation. Although that was deemed “un- reasonable” at first, Sepulveda said they eventually came around.

When Tomlinson was seven, his father sent him to a child guidance counselor out of concern. He said that his dad, only 28 at the time, was acting in the best way he knew, whether or not he knew of his son’s sexuality. The psychiatrist told his parents he was going to be fine. The matter was left at that until his late twenties.

His coming out conversation, at the age of 28, was less about the fact of his sexuality (which he had already come to terms with himself) and more about wanting his family’s acceptance of his first partner, David. From the moment he revealed his sexuality, his mother was supportive and insisted on knowing whom he was with.

His grandmother, with whom he was also close, met David as soon as they started spending time together, and ended up bridging the gap between Tomlinson and his father. She called him at home one night, already aware of why he hadn’t celebrated Thanksgiving with the family for two years in a row, and reassured him. It was the kind of moment that many newly out young people dream about.

“She said, ‘You will come up to my house for Thanksgiving and you will bring David and there will be no questions,’” Tomlinson said. “She said, ‘you and I have our own relationship, and your father can deal with this. If he wants to come, he is welcome to.’”

As it turned out, they discovered a range of common interests, and, as he was leaving that night, Tomlinson’s dad slipped a note in his pocket where he had written, “I really like David.”

Once Tomlinson’s parents saw how much Sepulveda and Tomlinson care for one another, and how deep their affection is, the couple’s relationship earned their full acceptance and respect. That happened after they spent a week together with the couple on Salt Spring Island a year after they tied the knot in 2004.

They both turn 50 this year, and after the election (successfully re-electing Pres. Obama, they hope), they plan on wrapping up some other projects and finding a way to spend six months or so inwardly focused. Both men were forthright in acknowledging their own character flaws–Sepulveda stated that his pot stirring has rubbed some people the wrong way, while Tomlinson acknowledged that he has been perceived as aloof– and that the work of being better is ongoing. The conversation that began almost 13 years ago, and the pursuit of their common interests, will continue in a new way.

“For me, I have a wedding band and I refer to Steven as my husband. Just the other day, someone said, ‘you’re so brave. You always refer to Steven as your husband,’” said Sepulveda, who doesn’t see it as bravery. “But in the straight world, that’s the perception.”

In one of Tomlinson’s plays, Curb Appeal, there’s a line that says, “You must not buy the house until you figure out what the fantasy is.” Can you imagine raising a family in that house? Or can you envision throwing certain types of parties? Sepulveda is right that the analogy works for relationships: you can’t settle on a mate until you also figure out what that par- ticular fantasy is about.

“I saw Steven, and he was very involved in the church and the university. He had friends who sat around and had the kinds of conversations I wanted to have.”

Everyone hopes for that type of aha moment. Even with the proliferation of gay characters and themes in popular culture, for many younger LGBT people, there still aren’t a lot of people whom they can personally look to as role models when it comes to building strong, long-term relationships. Pop culture doesn’t replace real-time mentoring–which is exactly what couples like Sepulveda and Tomlinson are doing every day. This makes the successes, personal and professional, that they’ve achieved all the more resonant with the next generation.

Their 21-year-old cousin, who is gay, stayed with them over the summer for an internship; it afforded him a window into gay life not available in rural Oklahoma. Like many others his age, he is searching for the right path, discovering where and how he will make his mark, and looking to his peers and his close relatives for guidance. “He said, ‘I wanted to come live with you guys this summer, because the gay guys that I know tell me that monogamous faithful gay relationships don’t exist,’” Tomlinson said. “I thought, who told you that? Just because you haven’t seen one doesn’t mean it does not exist.”

Sepulveda said that while all relationships take work, the payoff for them is that their interests–building community partnerships, expanding economic opportunities and prompting civic engagement–continue to mesh all these years later.

“Don’t seek a relationship that satisfies part of you. You want someone who you can be your whole self with,” said Tomlinson. “How dangerous to give advice. Talk about everything, even stuff that’s uncomfortable. Take the risk of being honest with the other person sooner than it seems reason- able. Don’t settle for something that’s less than honest and less than wholehearted.”